Opinion | Uncertainty has become the new normal as the era of Moore’s law draws to a close

‘When a product’s performance is improved beyond a singular dimension, as historically dictated by Moore’s law, roles and responsibilities blur’

Last Tuesday, the world’s biggest chip maker, Intel, whose brand is synonymous with personal computers and laptops, announced that its former chief executive Paul Otelini had passed away in his sleep at the age of 66. As the fifth chief executive of the company, Otelini presided over the period of largest growth in the company, raising the annual revenue from US$34 billion to US$53 billion in 2012. In fact, more money was made under his eight year reign than in the previous 37 years of Intel’s existence. No other company can fire out a better and faster microprocessor, the engine that spurs into motion when you turn your computer on.

But the dominance of Intel is as much about its inventiveness as its ability to predict product advancement. No other industry manages to engineer miracles with such absolute transparency. We tend to perceive innovation as something uncertain, and progress made by scientists can be slow at times. Yet, that’s not how Intel behaves. It’s clockwork; it’s anything but ambiguous.

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore made a bold prediction about the exponential growth of computing power. From the vacuum tube to the discrete transistor to the integrated circuit, the miniaturisation of computer hardware had progressed apace. Extrapolating the trend, Moore asserted that the number of microchip transistors etched into a fixed area of a computer microprocessor would double every two years. Since transistor density was correlated with computing power, the latter would also double every two years. As improbable as it might have seemed, Intel has since delivered on this promise, immortalising “Moore’s law.”

It’s difficult for anyone to fathom the effects of exponential growth. Take an imaginary letter-sized piece of paper and fold it in half. Then fold it a second time and then a third. The thickness of the stack doubles every time. If you manage to fold the same piece of paper 42 times, it will be so thick that it stretches all the way to the moon. That’s exponential growth. Exponential growth explains why a single iPhone today possesses more computing power than the entire spacecraft for the Apollo moon mission back in 1969. Without Moore’s law, there would be no Google, no Facebook, no Uber, no Airbnb. Silicon Valley would just be like any other valley.

When I was at a conference in Israel, a former Intel executive told me that Gordon Moore could get “rather philosophical” about the future of Moore’s law. When asked by his staff when this amazing trajectory might end, the co-founder responded, “Nothing grows exponentially forever.” And indeed, Intel was no exception.

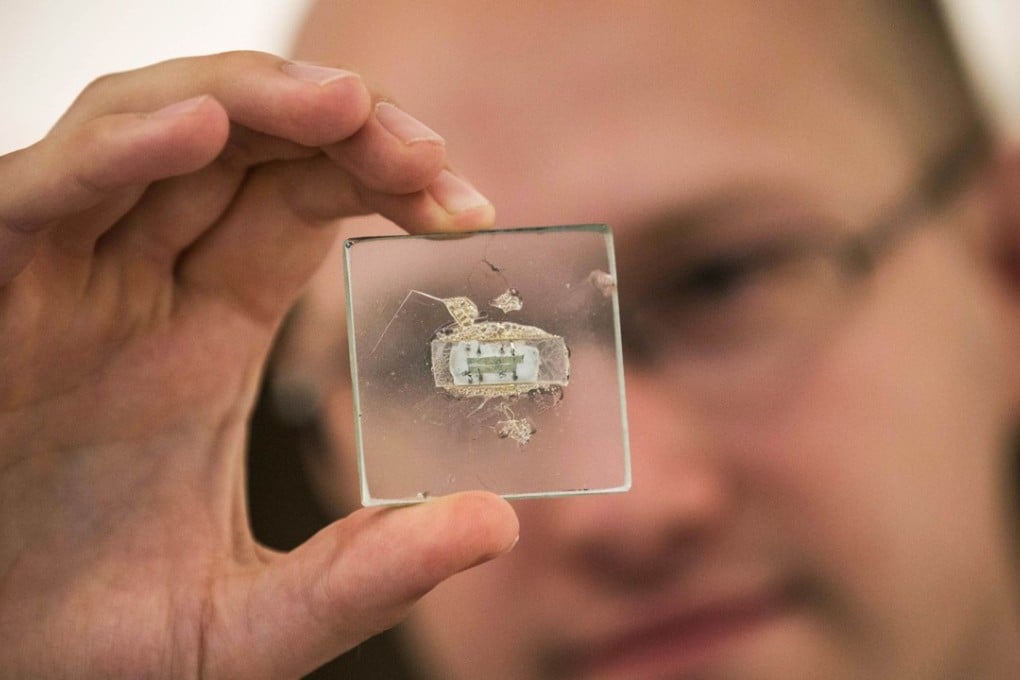

In 2016, Intel disclosed in a regulatory filing that it was slowing the pace of launching new chips. Its latest transistor is down to only about 100 atoms wide. The fewer atoms composing a transistor, the harder it is to manipulate. Following this trend, by early 2020, transistors should have just 10 atoms. At that scale, electronic properties would be disturbed by quantum physics, making any devices hopelessly unreliable. Samsung, Intel, and Microsoft have already shelled out US$37 billion just to keep the magic going, but soon enough, engineers and scientists will be hitting the fundamental limit of physics.