How Sun Yat-sen shaped Penang in Malaysia and influenced the lives of its Chinese residents

Little was known about the Chinese revolutionary’s time in Penang until Malaysian leader Mahathir Mohamad’s 2001 visit to an exhibition dedicated to Sun drew attention to his influence and legacy

“We are Hakka Chinese, from Huizhou,” one man in the congregation says of his ancestry in the Pearl River Delta, some 2,500km away. This kind of sentiment is typical in Malaysia, where the huaqiao (overseas Chinese) maintain an identity sourced from a distant locale, one they may or may not have even visited. In many ways these scenes of veneration recall a China largely vanished back home, a phantom dragon haunting the Nanyang, as the Chinese have long dubbed coastal Southeast Asia.

Penang is the only state in Malaysia with a Chinese ethnic majority, but it was not always that way. Arriving by ferry, the first sight is of the old colonial port known as Weld Quay: the Malayan Railway Building Clocktower just ahead of bank-lined Beach Street, which leads to the 18th century Fort Cornwallis. Penang was once Prince of Wales Island, acquired from the Sultan of Kedah by the British East India Company in 1786 and promptly established as a Southeast Asia entrepôt.

But it is the Chinese who have shaped George Town in their own image, a warren of arcade-lined streets wiring together a dizzying array of clan association buildings with names such as Tan (Chen) or regions and dialect groups like Teochew (Chaozhou), while a plethora of elaborate temples accommodate the pantheon of Chinese gods, saints and folk heroes.

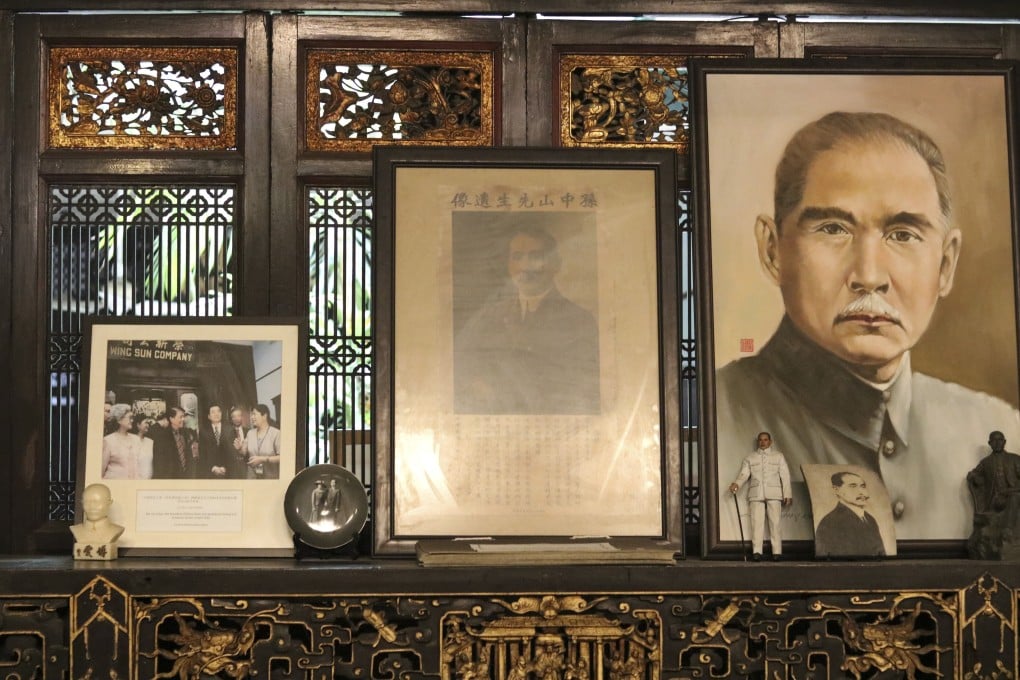

One image, though, neither ancient nor ethereal, is festooned across old George Town, a stoical face suspended beside shops and old houses, watching over Penangites like a benevolent uncle. It is a countenance more associated with revolution and republicanism than any Buddhist fables or Taoist immortals still revered in Malaysia; it is the face of Dr Sun Yat-sen.