Director’s cut: why it took 12 years to make ‘NOWHERE’ – film of Greek choreographer’s innovative show

- Dimitris Papaioannou features clips from his 2009 dance-theatre production in film to be shown on Friday and Saturday at Hong Kong’s New Vision Arts Festival

- Recording of central scene in imaginative show, which examines life’s sorrows and human possibilities, went viral online with more than 2.5 million views

A film recording of the central scene of Greek director and choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou’s imaginative 2009 dance-theatre production, NOWHERE, went viral after being posted on social media in June 2014 – attracting more than 2.5 million views.

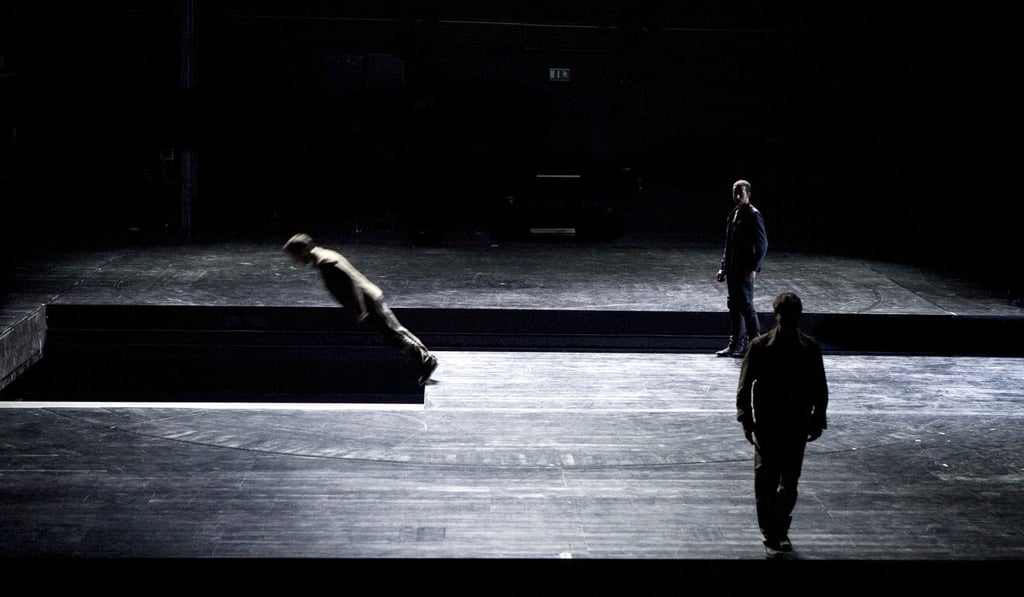

That particular scene from the thought-provoking show examining themes such as life’s sorrows and human possibilities – featuring performers as they navigate their way past onstage spatial challenges, including slowly moving, carefully choreographed, cascading lines of light rigs and gantries – was dedicated to the memory of Pina Bausch, a globally renowned German contemporary dance choreographer, who had just died aged 68.

The film shows the full version of the performance, but from different perspectives. The editing itself is a new dance partner in the dance piece: maybe the most important dance partner

The Athens-born Papaioannou, originally a painter and comics artist before switching to the performing arts, who is also known as a performer and designer of stage sets, lighting, costumes and make-up, had filmed the scene while recording all 79 performances of the two overlapping 2009 shows staged daily in his home city.

The full film, NOWHERE (Director’s Cut), which Papaioannou created by editing together clips from the original stage performances, is being screened for Hong Kong audiences for the first time as part of the city’s New Vision Arts Festival 2021 at Hong Kong City Hall, in Central, this Friday and Saturday.

Papaioannou, best known for creating the opening and closing ceremonies at the 2004 Athens Olympics, says editing the footage felt similar to bringing an extra participant into the creative experience.

“The film shows the full version of the performance, but from different perspectives,” he says. “The editing itself is a new dance partner in the dance piece: maybe the most important dance partner.”

Creating the film from footage Papaioannou recorded with a handheld high-definition camera proved a learning experience for him because he had never been shown how to do editing.

I kept recording the shows from various angles. In the editing process I found ways to make the two-dimensional take on a three-dimensional show richer through the points of perspective we could have

“I kept recording the shows with my camera from various angles: I ended up with material I didn’t know what I was going to do with,” he says.

“But in the editing process, as I learned, I found ways to make the two-dimensional take on a three-dimensional show richer through the points of perspective we could have. Maybe this change of perspective could replace the distance we feel from the live version when we’re watching the film.”

He says he had no particular approach when choosing footage for the final film. “[The scenes] just had to create an emotion that seemed appropriate – the same way that I compose a live show not having a system,” he says. “Whatever seemed to work, I did.”

NOWHERE – originally commissioned to inaugurate the renovated main stage at the Greek National Theatre – was conceived as a site-specific project to celebrate the nature of theatre and explore the idea of performance as a machine that mirrors human life.

Papaioannou says he called it NOWHERE because a theatre space – or “correct stage machine” as he describes it – “[is] a ‘no place’ that can become any place depending on the show and depending on the set design”.

[The film scenes] just had to create an emotion that seemed appropriate – the same way that I compose a live show not having a system. Whatever seemed to work, I did

He choreographed the space itself by programming new stage mechanisms – bringing moving structures onto the stage, with the 26 performers measuring and marking out the space with their bodies.

NOWHERE’s overlapping shows brought audiences face-to-face, with people attending the second show entering from the back of the stage believing it was the start of the performance, but ending up on stage at the end of the first show.

The audience watching the first show saw a group of people occupying the stage at the end of the performance, followed by the lights above the seats in the auditorium being turned on so both audiences could see each other.

“For one moment we had one audience face the other audience in a mirroring effect,” Papaioannou, who has retained the interaction between the audiences in the film, says. “The idea of the stage as a mirror runs throughout the show.”

He says the experience of people while watching the film is deliberately very different from that gained when watching the live show.

“There’s a big challenge in how we document live performances because the aim is for future students to be able to analyse the structure of the show,” he says. “At the same time, the way that it’s filmed and the way that it’s edited has to somehow create interest and emotion in this new medium that is film.”

For one moment we had one audience face the other audience in a mirroring effect. The idea of the stage as a mirror runs throughout the show

New Vision Arts Festival is one of the main partners that commissioned Papaioannou to release his film this year – 12 years after the original shows.

He was invited to finish editing the full film version of NOWHERE and present it at Hong Kong’s annual festival – which introduces audiences to pioneering, trendsetting and groundbreaking performing arts from around the world – after plans for the event to stage his latest work, Transverse Orientation, were postponed because of the continuing Covid-19 pandemic.

“When there was an interest and a commission, I revisited my short, early edit of the footage, working intensely in Athens this summer to update it,” Papaioannou says.

The film, which lasts about 40 minutes, contains scenes of nudity, so no children below the age of 16 will be admitted. The screenings will be followed by a talk by local artists.