Angus Donald on wild parties, war zones and finding love through a psychic

Angus Donald’s reporting took him from Hong Kong to Kabul. When he finally slowed down, he found love because of a psychic

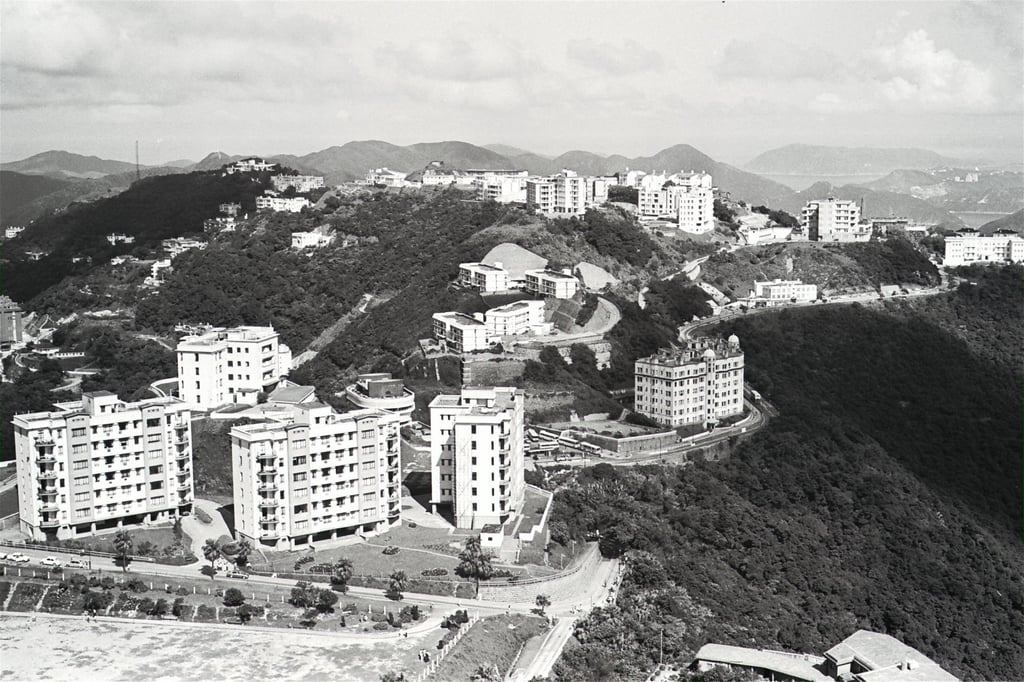

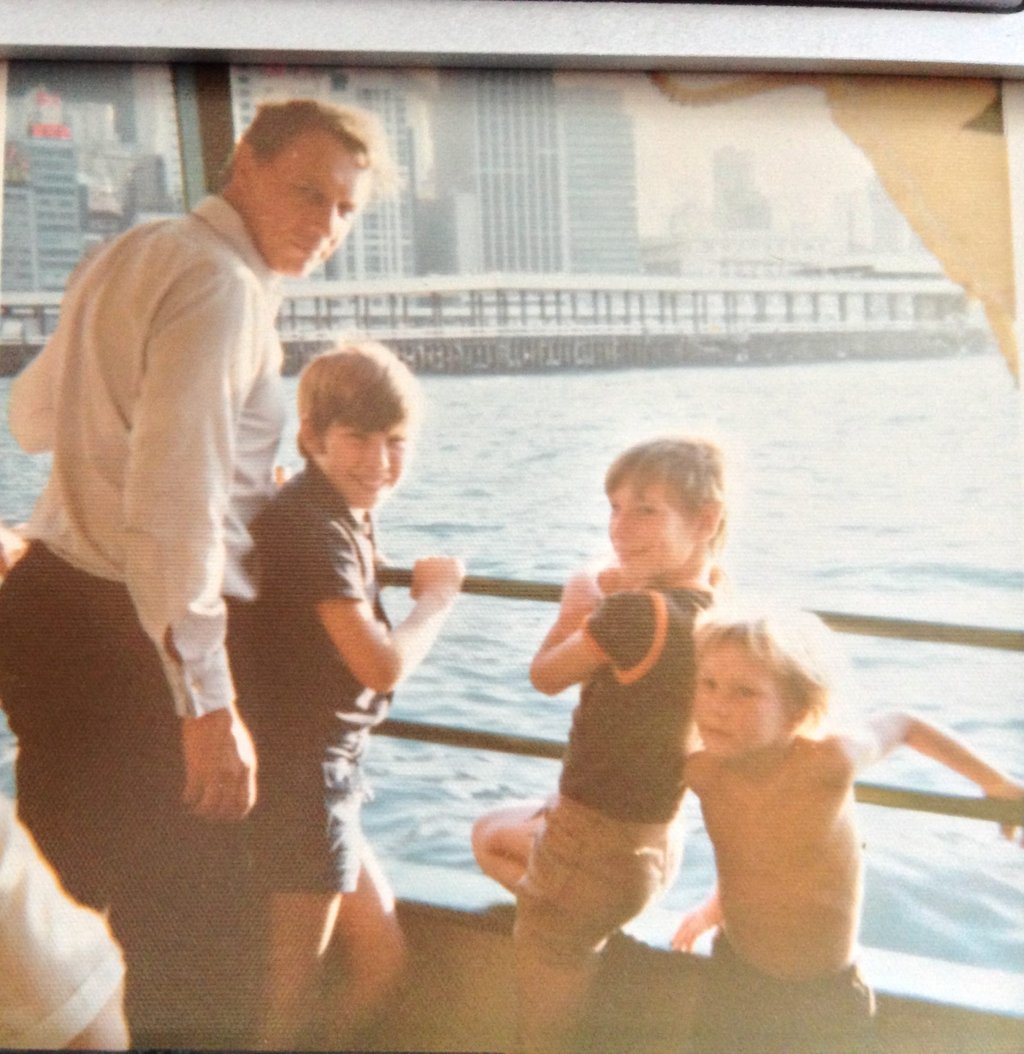

WE LIVED ON THE PEAK, in a large white house on Mount Kellett Road. I remember camping on High West (Sai Ko Shan) with my brother John one summer. I was about 10 and he was 14. We marched off with all our gear, slept on the bare mountainside, made a fire and cooked bacon. I discovered afterward that my mother had been freaking out the whole time. The radio had reported that an escaped criminal was at large in the vicinity. But Hong Kong in the 1970s was generally a happy time. I recall junk trips, picnics and visits to a bustling market where I bought a tiny transistor radio, my prized possession.

AFTER LEAVING MARLBOROUGH, I went on holiday to Greece and didn’t come back. When I ran low on money, I found work as a fruit picker in Crete. Actually, most of the time I hung out on the beach, chatting up tourist girls and drinking. I abruptly cancelled my plans to read chemistry at Southampton University and, inspired by John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row (1945) and Tortilla Flat (1935), embarked joyfully on a delightful but penniless career as a beach bum. Being perpetually broke palled after a year, however. I remember one miserable period of three days in the autumn when me and my friends just lay in our room, starving, drinking black tea and occasionally venturing out to steal oranges off trees for sustenance.

WHEN I’D HAD ENOUGH of living on Cannery Row, I got myself back to England in the mid-1980s, hitchhiking through Yugoslavia, Italy and France, and finally got my academic s*** together, applying to Edinburgh University. I read social anthropology and, in my third year, the university sent me to Bali to do fieldwork for my dissertation. I hung out with traditional healers in a remote mountain village with no electricity. After university, I flew to Beijing to see my folks. I had no plan, but a vague idea that I wanted to write for a living. After a few months of shoestring travel from the Great Wall to Yunnan, I ran out of money, so I got on a train heading east to Hong Kong to look for work. I arrived with a backpack full of dirty clothes and about US$10 in my pocket and was lucky enough to get a job teaching English.

HONG KONG IN THE EARLY 1990s was a fantastic place to be a brash young Englishman. I got a job on a magazine, proofreading and writing small bits of copy, and eventually got a position on The Standard newspaper, writing for their weekend magazine. I spent four happy years in Hong Kong, drinking too much in Lan Kwai Fong and Wan Chai at night, and bashing out features by day. I made many fantastic, creative friends and enjoyed uncountable wild parties, pursued many lovely girls and got very little sleep. I was also nearing 30 and knew the partying had to stop. I returned to London and got work at The Sunday Telegraph Magazine, and after a few years I moved to the Financial Times. I missed Asia, however, and when the FT offered me a job as their stringer in Delhi, I bit their hand off. But the job turned out to be less fun than I had expected. I was bored and lonely in Delhi, and my London boss hated me, so when 9/11 happened, I resigned and went up to Pakistan to freelance.

I WANTED TO SEE the Afghan war first-hand. It seems insane now but I had a thing about testing myself, my manhood, in those days, seeing how far I could push my luck. I was in Islamabad for a few weeks, waiting to get into Afghanistan and writing for any paper that would take my copy. It was a bizarre, terrifying time. I remember covering an anti-Western demonstration in Peshawar, tens of thousands of Pashtuns chanting, “Death to the UK!” I was running beside the mob, tripped and was surrounded by a gang of Taliban. That was one of a handful of times in my life that I thought, “This is it. I’m dead.” But, on seeing me fall, the gang, who moments before had been calling for my blood, helped me to my feet and took me to a nearby chai shop, where I was given sweet tea and a good deal of genuine sympathy.

I GOT INTO AFGHANISTAN, and reported from Jalalabad for a few weeks. I was in the bomb-eviscerated caves of Tora Bora just a day after Osama bin Laden fled them (in 2001). But freelancing in a war zone is not practical. I had no backup and little money. One night, when I came back from the battlefield after an 18-hour day and banged out a piece for The Independent, I had an epiphany. I had been mortared and machine-gunned, I had eaten nothing all day (it was Ramadan) and I was exhausted, staying in a half-built hotel, sleeping on concrete. I knew I would be paid £70 (HK$790 in December 2001) for that article. “This doesn’t work,” I thought. “I’m going to get my leg blown off, or be shot, for £70.” So I returned to London and got a job at The Times as a subeditor on “Body & Soul”, a Saturday section aimed primarily at women. It was not really my thing, but at least nobody was trying to kill me.

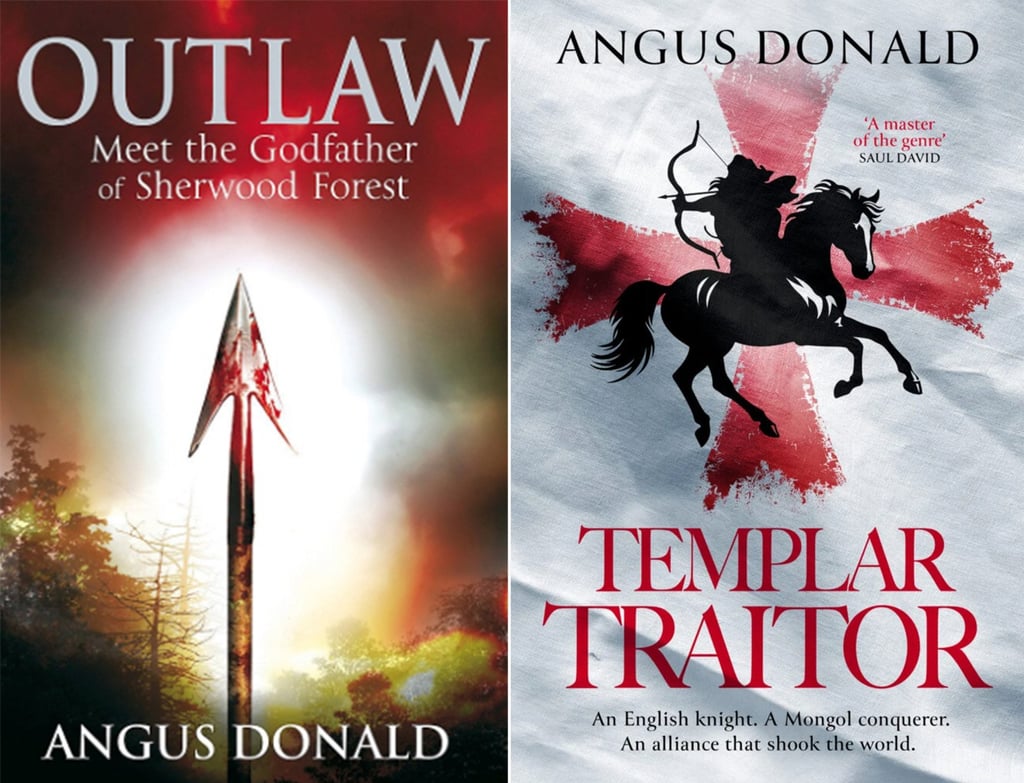

AT THAT TIME, I was nearing 40 and realised I had nothing: no money, no woman, no house and a job I didn’t much care for. So I worked out what I really wanted to do, and that was to write historical fiction in the style of Bernard Cornwell, a novelist I greatly admired. It took me five years to get it together, getting up at four to work on my novel before heading into The Times to edit other people’s copy. But my first book, Outlaw (2009), a dark tale about a gangster-ish Robin Hood, was a success. That one book has sold over a quarter of a million copies so far. I still get a few thousand in royalties annually from it 16 years later. Earlier this month, I published the 11th book in the bestselling Outlaw Chronicles series.

I DID ONE OTHER significant thing at The Times. One of the editors gave me a flier advertising a “Psychic Love Coach” and told me to go and do a story on her. “Make it funny,” the editor said. “Be as mean as you like.” So, I presented myself at this love coach’s west London front door. I didn’t knock, chuckling to myself that if she were truly a psychic she would know I was there. Ho-ho. The psychic turned out to be a Hong Kong person – a lovely half-Chinese, half-Irish lady, who read my fortune in a dog-eared pack of playing cards. She made me hold a pair of “magic” crystals and meditate, chanting “I deserve to find love! I will find love!” every morning and evening. Then she made me go speed dating. That was how I met my wonderful wife, Mary. I invited the psychic to our wedding, and Mary and I have two teenage children and live in a medieval farmhouse in Kent. We celebrated our 20th wedding anniversary this year.