Moving through life without collecting: lessons from a nomadic childhood

PostMag writer Fionnuala McHugh has lived a life free of clutter – and feels all the better for it

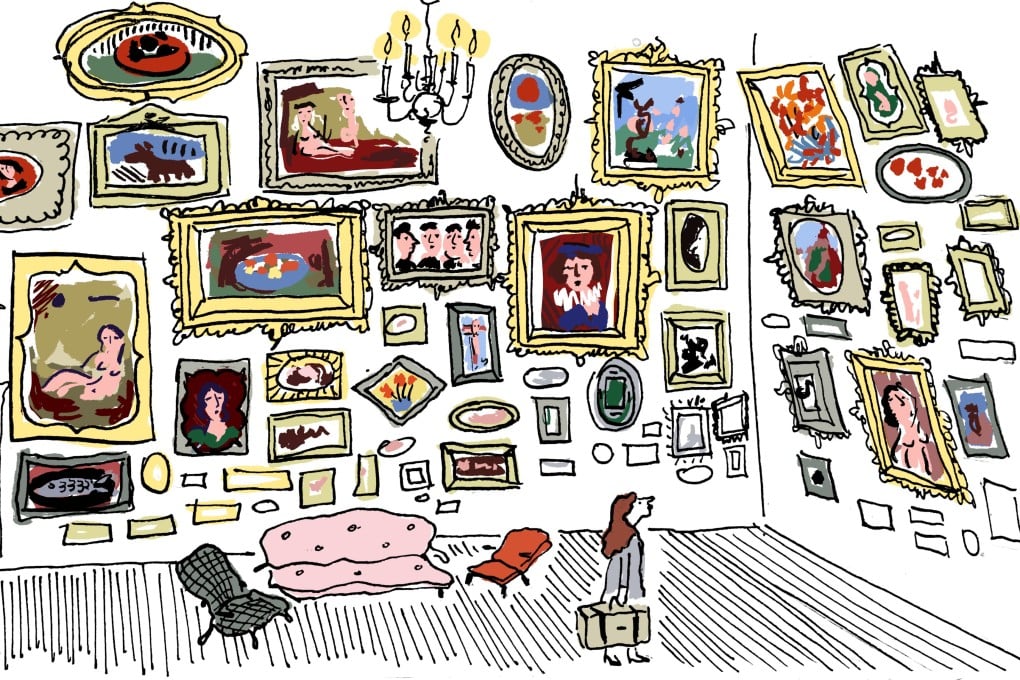

In 1992, a British newspaper sent me to New York to interview a man called Paul Mellon. He was 85 and was said to have been wealthier longer than any other living American; the family fortune flowed from the Mellon Bank, founded in 1870. He was also, according to a London gallery owner, “the last civilised collector”. In his Manhattan town house off Park Avenue, one of his seven residences, there was a Canaletto, a squad of Constables, a Stubbs, some Bonnards; the dining room alone had a Sargent, a Cézanne, a Vuillard and a Degas. We lunched, just the two of us, under a Monet. The paintings clustered around, watching.

Mellon had written a memoir, Reflections in a Silver Spoon (1992), and for three hours he talked about his unhappy childhood, his two wives, his analysts, his horses, his children (“We have a nice rapport when we meet”). He was both extremely courteous and one of the least emotional interviewees I’ve ever met. His father, Andrew Mellon, a former United States Secretary of the Treasury, had been a famous collector who had established Washington’s National Gallery of Art. The son had continued the philanthropic tradition but when I asked, he said no, there had never been a thrill in his major acquisitions. As a young man, he’d simply loved English sporting prints because he loved horses. Later, he admitted, “I bought paintings as though they were apples or grapefruit.” There was no passion. Maybe that’s what the London gallery owner meant.

Afterwards, out on New York’s less refined streets, I remember drawing a few deep breaths. There had been something oppressive in the thinginess of the crammed interior. Since then, I’ve interviewed many collectors, from the royal family of Liechtenstein in their Vaduz palace to tax-accountant-cum-world-class-textile-expert Chris Hall in his flat on Hong Kong’s Peak, and no matter how beautiful the pieces, how solid the learning and how sincere the – universally prevailing – desire to leave a legacy, I’ve never fully understood the urge. Afterwards, there would always be an inhalation and I’d return to my non-palatial abode consumed with relief not envy.

When home is perpetually mobile, you have to be prepared