Global push for AI education leads world’s most powerful economies on divergent paths

All governments are racing to equip their citizens with AI skills, but their approaches vary wildly

Artificial intelligence isn’t just a concept from science fiction any more. As it becomes increasingly integrated into our lives, AI literacy – the ability to understand and interact with AI effectively – is more crucial than ever. Countries worldwide are now racing to educate their citizens in this field.

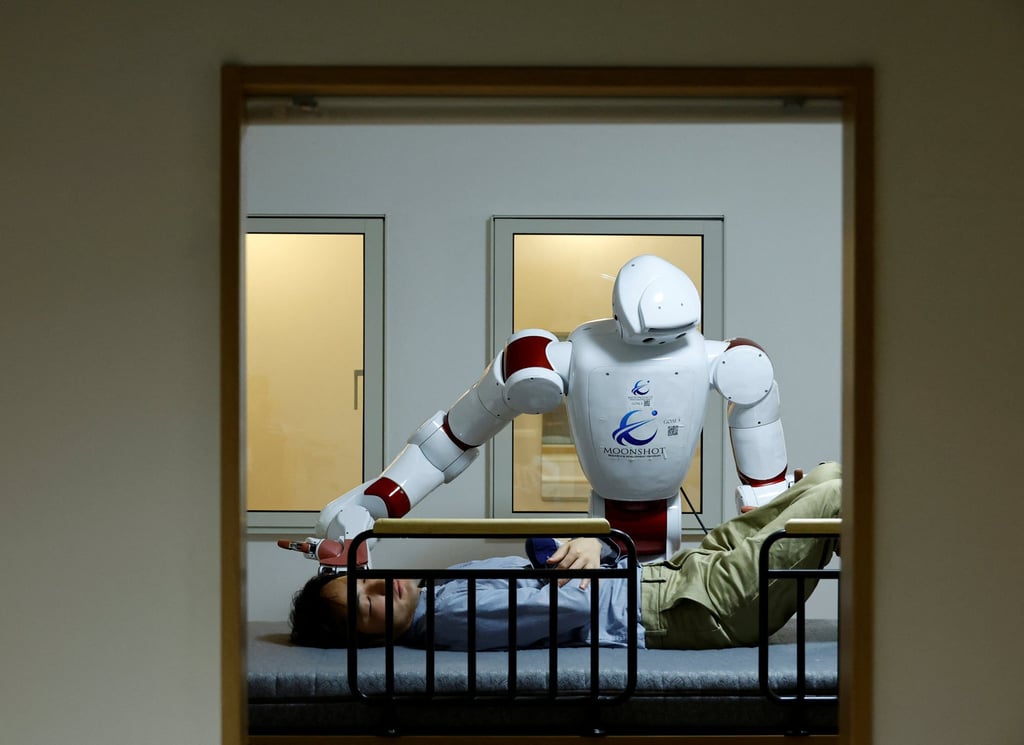

Consider the case of Japan, which is facing significant demographic challenges with nearly a third of its population aged 65 or older – for perspective, compare that to a more manageable 15 per cent in China. Japan is making a substantial bet on AI, hoping it can help maintain productivity and economic stability as its workforce shrinks.

However, it has considerable ground to cover. According to Stanford University’s 2025 AI Index Report, Japan’s private investment in AI in 2024 was only US$0.93 billion. This pales in comparison to the US (US$109.08 billion), China (US$9.29 billion) and the UK (US$4.52 billion), and is even behind regional players like South Korea and India.

To address this, the Japanese parliament passed the Act on the Promotion of Research and Development and the Utilisation of AI-Related Technologies in May, recognising AI technologies as “fundamental … for the development of Japan’s economy and society”.

“The truth is that every job will be affected by AI at some point,” says Liu Haihao, a machine learning researcher at Algoverse and founder of the non-profit Ternity Education. “But the bigger point is that AI literacy is crucial for everyone since we all interact with AI in our daily lives, even indirectly, due to social media algorithms and AI-generated content.”

Japan’s older workforce, however, might face an uphill battle in achieving widespread AI literacy. Liu notes, “In Southeast Asian countries where 50 to 60 per cent of the population are under 30, this is an advantage in terms of having a workforce with high digital and AI literacy, to fully leverage new technologies.”

Despite Japan’s efforts, most eyes remain fixed on the US and China, whose combined private AI investments far outstrip every other country in the world. These two global powers, however, have adopted vastly different philosophies on education around AI.

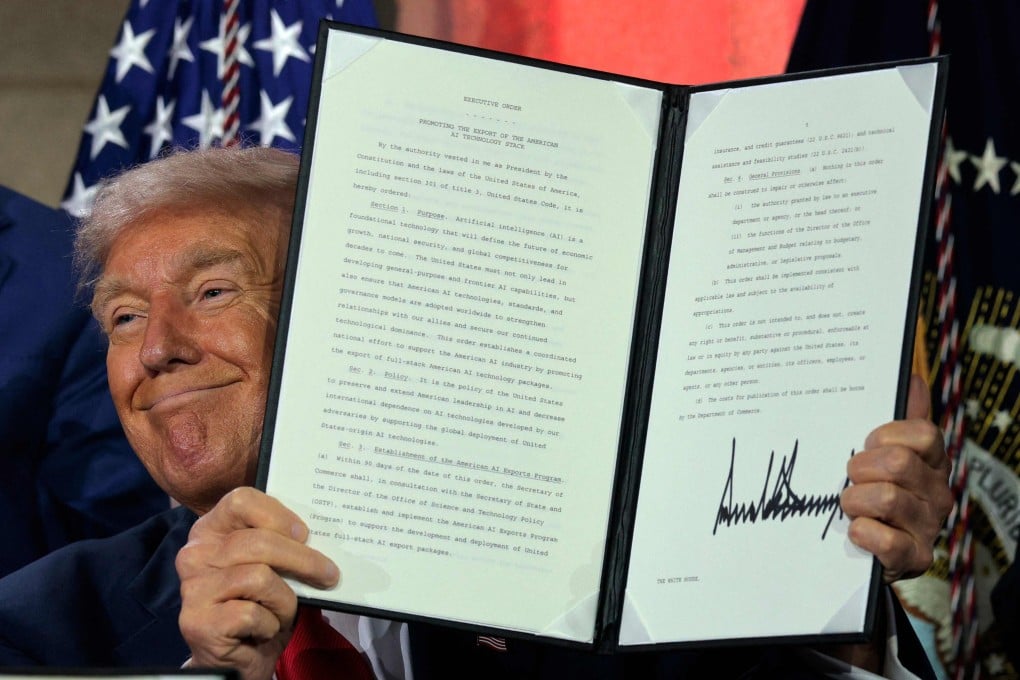

In the US, the federal government recently issued an executive order aimed at embedding AI learning throughout the K-12 (primary and secondary) education system. This new policy emphasises technical instruction, ethical reasoning and critical analysis, preparing students for a future where AI will be ubiquitous.

Liu highlights the importance of the White House’s recent “AI Education Pledge”, where over 60 companies, including tech giants like Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia and OpenAI, committed to providing AI education materials to K-12 students for the next four years. However, Liu also points out that the US’ education system is somewhat “piecemeal”, with federal authorities leaving many decisions to individual states. “This leaves a lot of gaps and disparities between states, as well as between public and private schools,” he explains.

China has adopted a markedly different approach characterised by centralised planning and rapid, mandatory implementation. Starting this autumn, every student from junior school onwards will receive at least eight hours of AI instruction per year. This initiative will integrate AI applications into teaching, textbooks and the national curriculum, with the ultimate goal of embedding AI fluency as a core part of citizenship and national identity.

Yet, despite China’s centralised and expedited policy, Liu cautions that its reliance on provincial and local education departments for implementation leaves ample room for inefficiencies, educational quality gaps and even corruption.

While China and the US often dominate the headlines, the European Union has been moving more cautiously. Last year, the European Commission passed the AI Act, which “requires providers and deployers of AI systems to ensure a sufficient level of AI literacy of their staff and other persons dealing with AI systems on their behalf”. However, the act notably “does not entail an obligation to measure the knowledge of AI of employees”.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, emphasised Europe’s ambition at the Artificial Intelligence Action summit in February, stating, “We want Europe to be one of the leading AI continents.” She dismissed the idea that China and the US are “too far ahead”, arguing, “Truth is, we are only at the beginning [of the race]. The frontier is constantly moving. And global leadership is still up for grabs. And behind the frontier lies the whole world of AI adoption. AI has only just begun to be adopted in the key sectors of our economy, and for the key challenges of our times.”